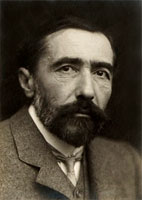

It is with a certain bitterness that one must admit to oneself that the late S.S. Titanic had a "good press."So says Joseph Conrad, author of Heart of Darkness, and former sailor in the British Merchant Marine. He wrote an essay called "Some Reflections on the Loss of the Titanic," published in the English Review in June 1912.

OK, he got the name of the ship wrong--it's actually (as you probably know) the RMS Titanic (Royal Mail Ship). But he had much to criticize in the way the Titanic disaster was reported and understood by people of his generation. This is indeed a very bitter essay.

The "good press" about the Titanic was the mass of stories and praise for the way people acted when the ship sank, putting "women and children first," being "British," and showing a stiff upper lip.

But that's not the heart of his criticism. The essay is rather dense, full of long, thick sentences and thundering accusations. Conrad's main argument, is that no one--no one--should have believed the ship unsinkable.

I ask myself whether the Marine Department of the Board of Trade did really believe, when they decided to shelve the report on equipment for a time, that a ship of 45,000 tons, that any ship, could be made practically indestructible by means of watertight bulkheads? It seems incredible to anybody who had ever reflected upon the properties of material, such as wood or steel.He also is dead-set against "floating hotels" like Titanic, where waiters outnumbered true seamen (like himself.) He compares the Titanic's sinking with the sinking of a smaller ship where there were no passengers lost. But that ship was different:

She was a ship commanded, manned, equipped--not a sort of marine Ritz, proclaimed unsinkable and sent adrift with its casual population upon the sea, without enough boats, without enough seamen (but with a Parisian café and four hundred of poor devils of waiters) to meet dangers which, let the engineers say what they like, lurk always amongst the waves; sent with a blind trust in mere material, light-heartedly, to a most miserable, most fatuous disaster.(Wow, that's all one sentence!)

Because of the hubris involved in creating and sailing these big ships, the deaths from the disaster should not be considered "heroic" in any way, Conrad writes. They should be considered victims.

I, who am not a sentimentalist, think it would have been finer if the band of the Titanic had been quietly saved, instead of being drowned while playing–whatever tune they were playing, the poor devils. I would rather they had been saved to support their families than to see their families supported by the magnificent generosity of the subscribers. There is nothing more heroic in being drowned very much against your will, than in dying of colic caused by the imperfect salmon in the tin you bought from your grocer.

And that’s the truth. The unsentimental truth stripped of the romantic garment the Press has wrapped around this most unnecessary disaster.Strong words.

For Conrad, the Titanic's sinking was just one more bit of evidence of a Heart of Darkness--not the one in Africa, but the one in the hearts of the people that created, sold tickets for, and managed the Titanic.

No comments:

Post a Comment